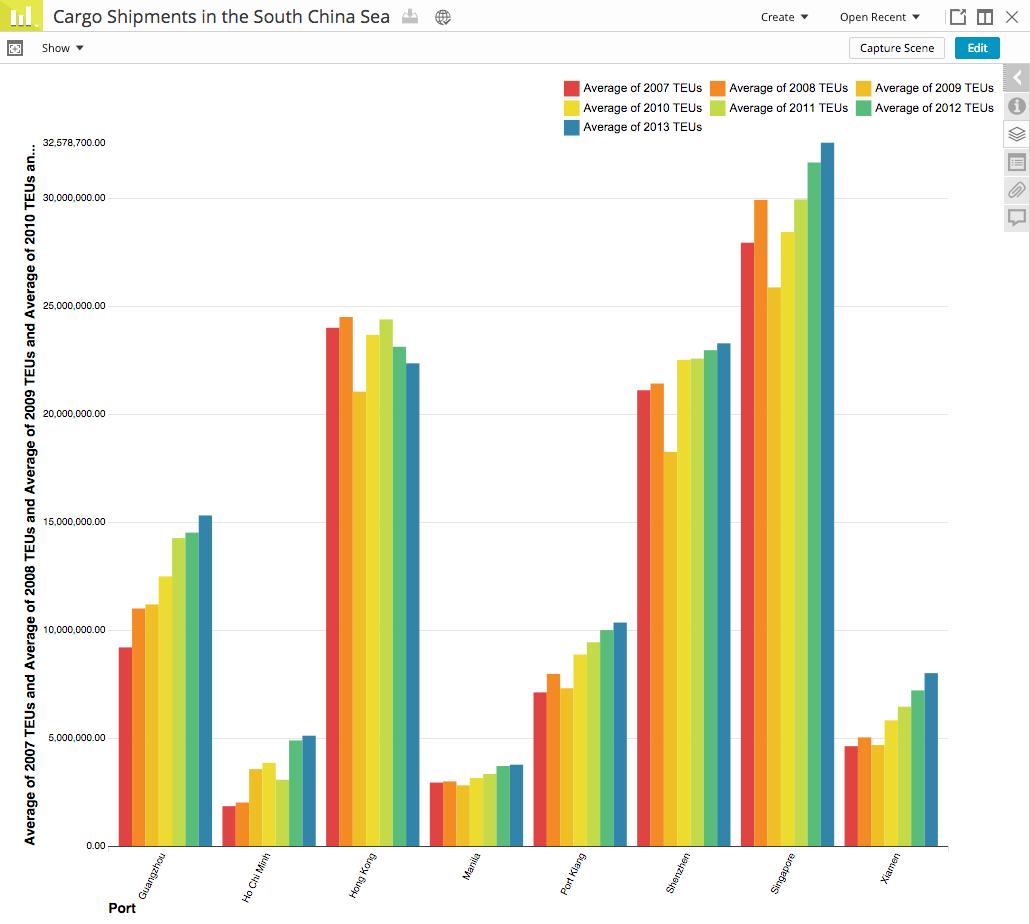

For centuries, the South China Sea between Taiwan and Malaysia has been an important thoroughfare for sea-based traffic heading to and from the lands neighboring it. Today, it is even more prominent—fishermen of at least half a dozen nations ply its waters for food, cargo valued nearly $5 trillion passes through every year, and as much as a third of the world’s oil trade (two thirds of natural gas!) passes through the Straits of Malacca en route to destinations in Japan, China, and other industrial centers around the world. New discoveries of precious mineral resources and fossil fuels buried under the seabed have aroused the interest of developers, and the Sea’s strategic location between so many developing nations, allies and rivals of the Western powers have kept American attention on it since long before President Obama announced his government’s ‘pivot to Asia’ in 2012.

For centuries, the South China Sea between Taiwan and Malaysia has been an important thoroughfare for sea-based traffic heading to and from the lands neighboring it. Today, it is even more prominent—fishermen of at least half a dozen nations ply its waters for food, cargo valued nearly $5 trillion passes through every year, and as much as a third of the world’s oil trade (two thirds of natural gas!) passes through the Straits of Malacca en route to destinations in Japan, China, and other industrial centers around the world. New discoveries of precious mineral resources and fossil fuels buried under the seabed have aroused the interest of developers, and the Sea’s strategic location between so many developing nations, allies and rivals of the Western powers have kept American attention on it since long before President Obama announced his government’s ‘pivot to Asia’ in 2012.

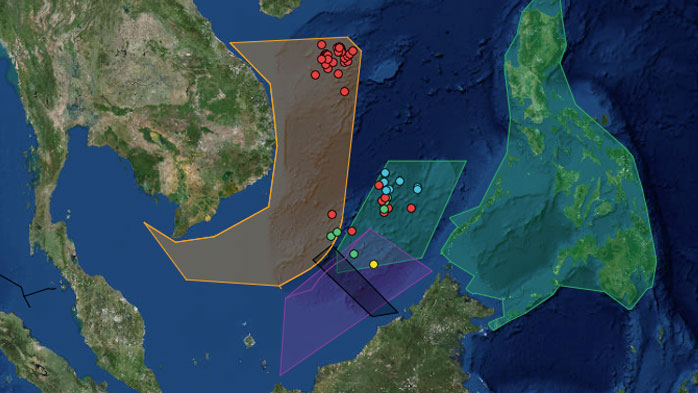

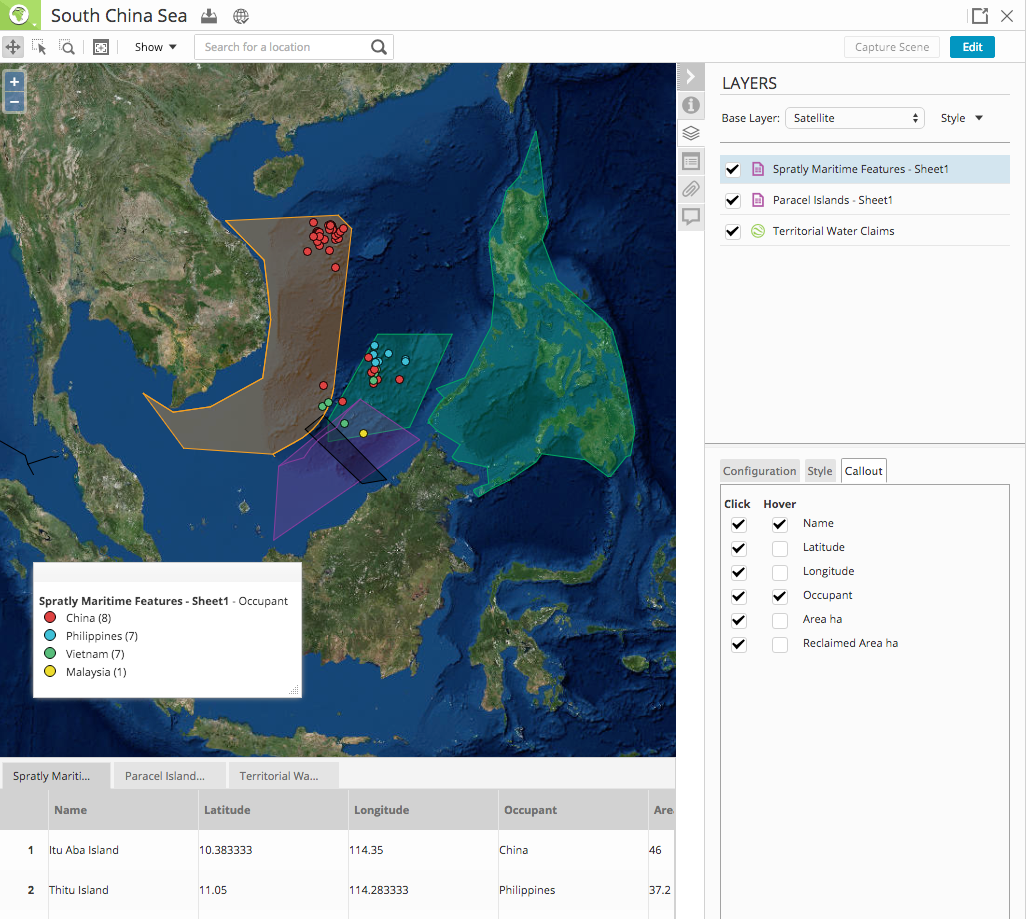

Political tensions around this bustling hub of commerce have been on the rise for years, however, and calming them will be no easy task. The competing territorial claims of China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei, Malaysia and Indonesia over what they consider to be their sovereign waters in the South China Sea have been the center of legal disputes and a few bloody skirmishes in the twentieth century. Every nearby coastal nation wishes to control as much of the sea, and the resources it conceals, as it possibly can. These disputes are complicated by the presence of several groups of small islands, reefs and rocks – the Spratlys, Paracels, and Scarborough Shoal – which have been the site of controversial land grabs that peaked in 2014. Thanks to the rules adopted by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the owner of these islands may be able to claim at least a twelve nautical mile radius around each one.

The topic of whose claims are the most legitimate, particularly in these island groups, has been the subject of heated debate in courts and political dialogue. Vietnam’s bid for ownership of the Spratlys and Paracels relies on its history of exploring and administrating them during the 18th and 19th centuries, while Malaysia and Brunei make limited claims encompassing only a few islands based solely on international law and the UNCLOS. The Philippines assert that the 1956 declaration of a sovereign nation in the Spratlys by a Filipino citizen, and its subsequent annexation by Ferdinand Marcos’ government in the 1970s, gives it a legal basis for ownership. By far the most disruptive claim in the area is that of the People’s Republic of China, which published a map in 1947 depicting the now-famous ‘nine dash line’ that claimed virtually all of the South China Sea on the basis of historical exploration.

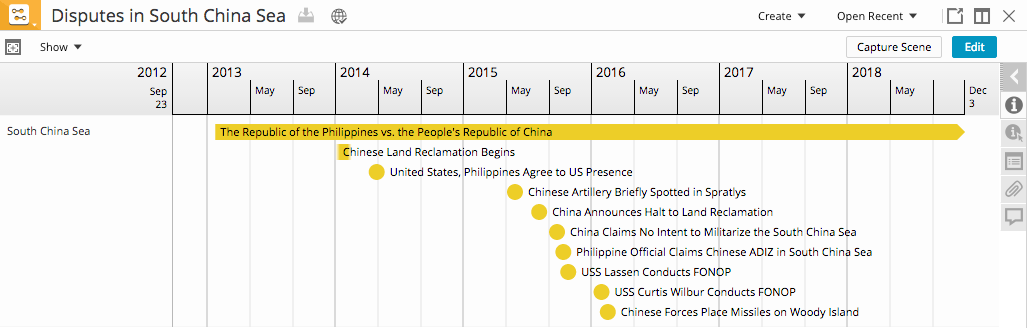

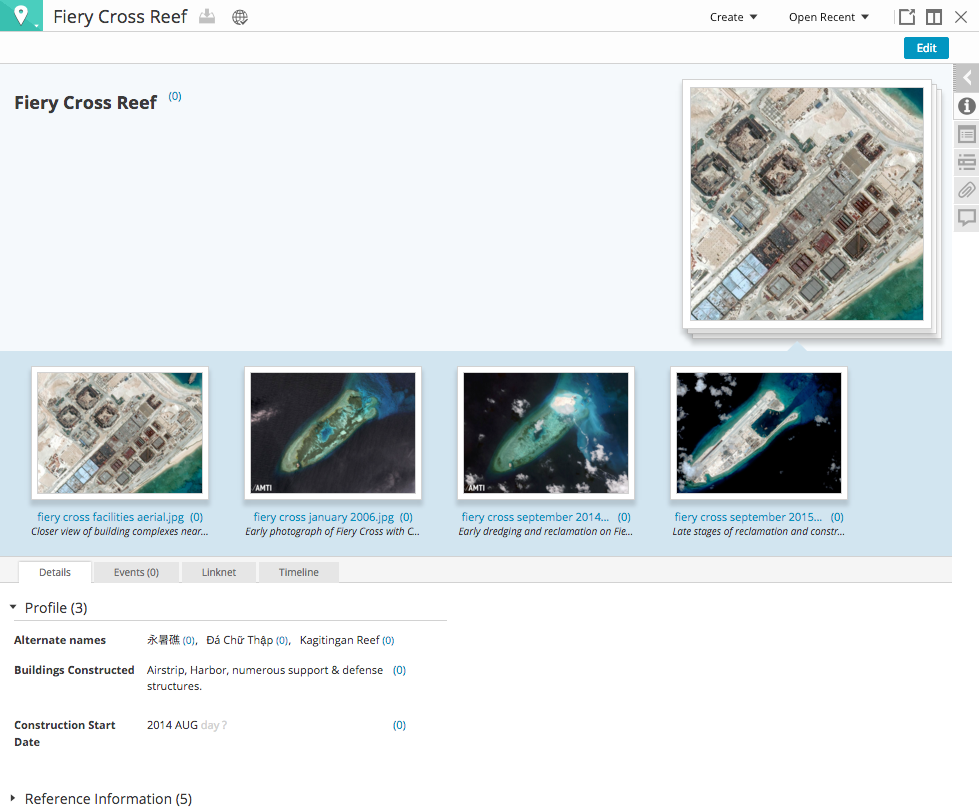

China has done much more than merely claim vast areas of the sea, however. Disadvantaged by its relatively late arrival to physically occupying land features, the PRC has used its economic and military might to change the facts on the ground by simply adding to, fortifying and tenaciously discouraging access to a series of rocks in the Spratlys. South Johnson Reef, Mischief Reef, and others have been transformed from shallow areas in the water into sandy islands with airstrips, barracks and surveillance towers spread over thousands of acres of new land. Although the People’s Liberation Army has been slow to militarize these new features, perhaps due to pressure from its neighbors and the United States, the door is open for installation of military hardware that could effectively turn the South China Sea into a fortress. Reports that Chinese forces have inconsistently enforced restrictions similar to an Air Defense Identification Zone, as already practiced over the disputed Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, have prompted concern among observers.

The future of the South China Sea, and the nations that lay claim to it, are in flux, but a number of possible turning points are fast approaching. When the Philippines’ case against China is resolved in the Permanent Court of Arbitration, will China recognize the decision or continue to ignore it? Will Australia and the United States continue freedom of navigation operations around Chinese isles despite the installation of defensive missiles in the Paracels? A decision by Chinese forces to more aggressively assert control, especially if it results in another confrontation between militaries, has the potential to spark a conflict that could devastate a global economy reliant on the goods and resources passing by Asia’s eastern shores.

Curious? Let's set up a free trial.

Try Savanna