Burundians protest against Pierre Nkurunziza’s illegal race for a third term in office. (Photo: AFP/Simon Maina)

Burundi escapes the notice of many international affairs observers. Their crisis is overshadowed by consistent headlines about Boko Haram and the Islamic State, yet it is no less critical.

Burundi’s story appeared to be one of redemption — recovering from the chaos of a genocidal civil war. For a time, it seemed as if the fledgling African nation could finally prosper under a democratic government.

“They told me that if we didn’t change our minds we would humiliate the president and that we were taking a big risk, that we were risking our lives and we would have to join the other side.” — Sylvere Nimpagaritse, Constitutional Court justice, explains to Agence France-Presse why he fled Burundi rather than approve a third Nkurunziza term.

Finally it seemed, a peace accord enshrined principles of tolerance and power sharing. However, cracks could be spotted in this facade of health since peace was declared in 2005. It now appears President Pierre Nkurunziza’s pursuit of a third term in office may mean the era of peace for the Republic will be short-lived.

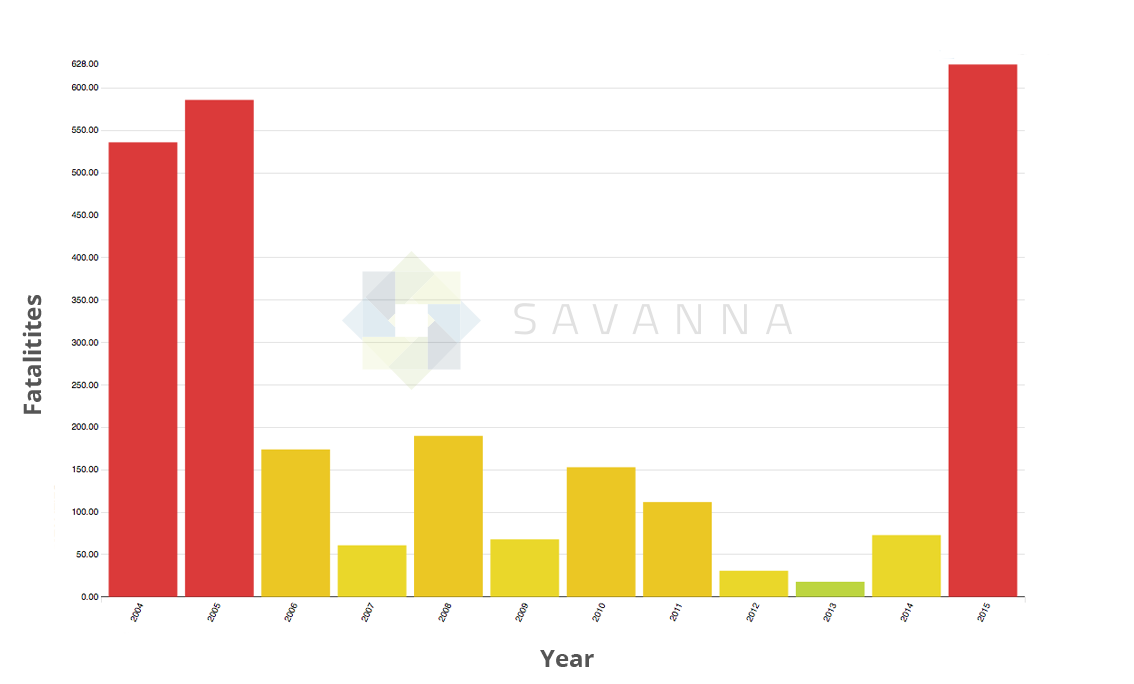

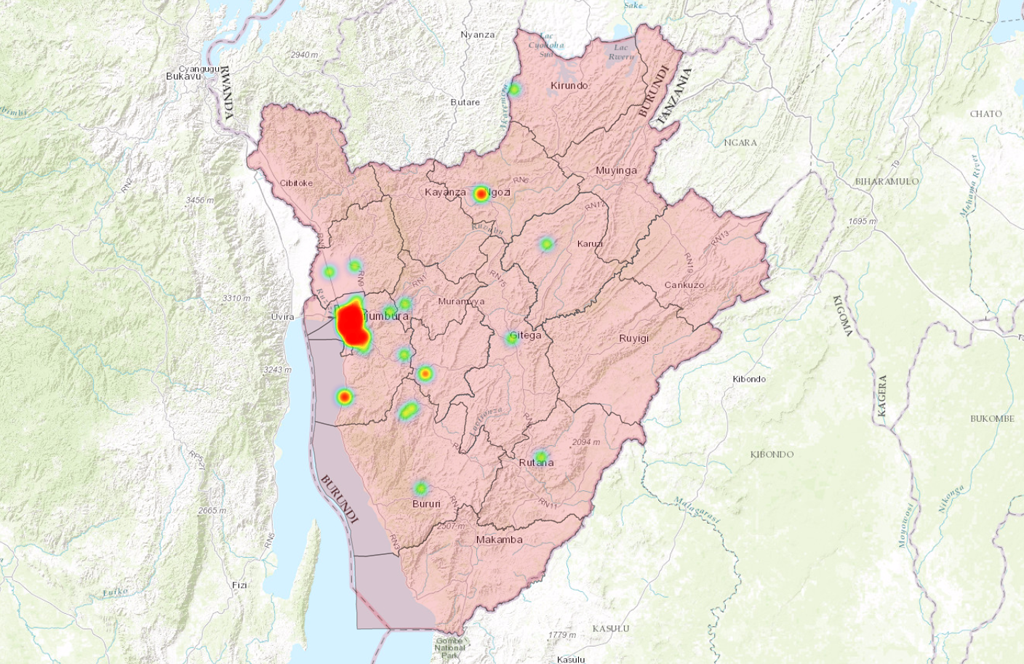

The comparison of President Nkurunziza’s past two terms and his third term so far, as measured by violence against civilians, is night and day. The University of Sussex’s ACLED Project, which compiles data on conflicts and crises, recorded nearly 600 violent incidents in Burundi, with 880 fatalities between 2006 and 2014. In 2015 alone, ACLED reported 470 violent incidents with 628 fatalities. [1]

Government forces and unidentified groups out of uniform attack mostly civilians incapable of armed resistance. The catalyst of this violence seems clear: an eruption of protests amidst rumors the President would unconstitutionally seek a third term in office. Protests have escalated since his formal nomination.

Forced disappearances, torture, and largely indiscriminate murder in broad daylight have been the regime’s response to both peaceful protests and guerrilla-style attacks on security forces.

“When the day comes and the order is given to go to work, there will be no time for feelings… If you act as an accomplice, hide them in your homes and under your beds, you will share their fate… We will kill you like we kill them.” — Senate President Reverien Ndikuriyo, promising retribution against those who harbor political dissidents in a speech dated November 2015. [2]

Although these killings and abductions do not strictly meet the legal criteria of a genocide, troubling language referencing the 1990s genocides has been used by the CNDD-FDD at all levels.

From Imbonerakure street thugs singing anthems that promise to cleanse refugee camps to the President of the Senate urging community leaders to expose dissidents and claim their property, the ruling party’s repeated invocations of the ethnic wars of the past send a message of intimidation: Support us or be silent.

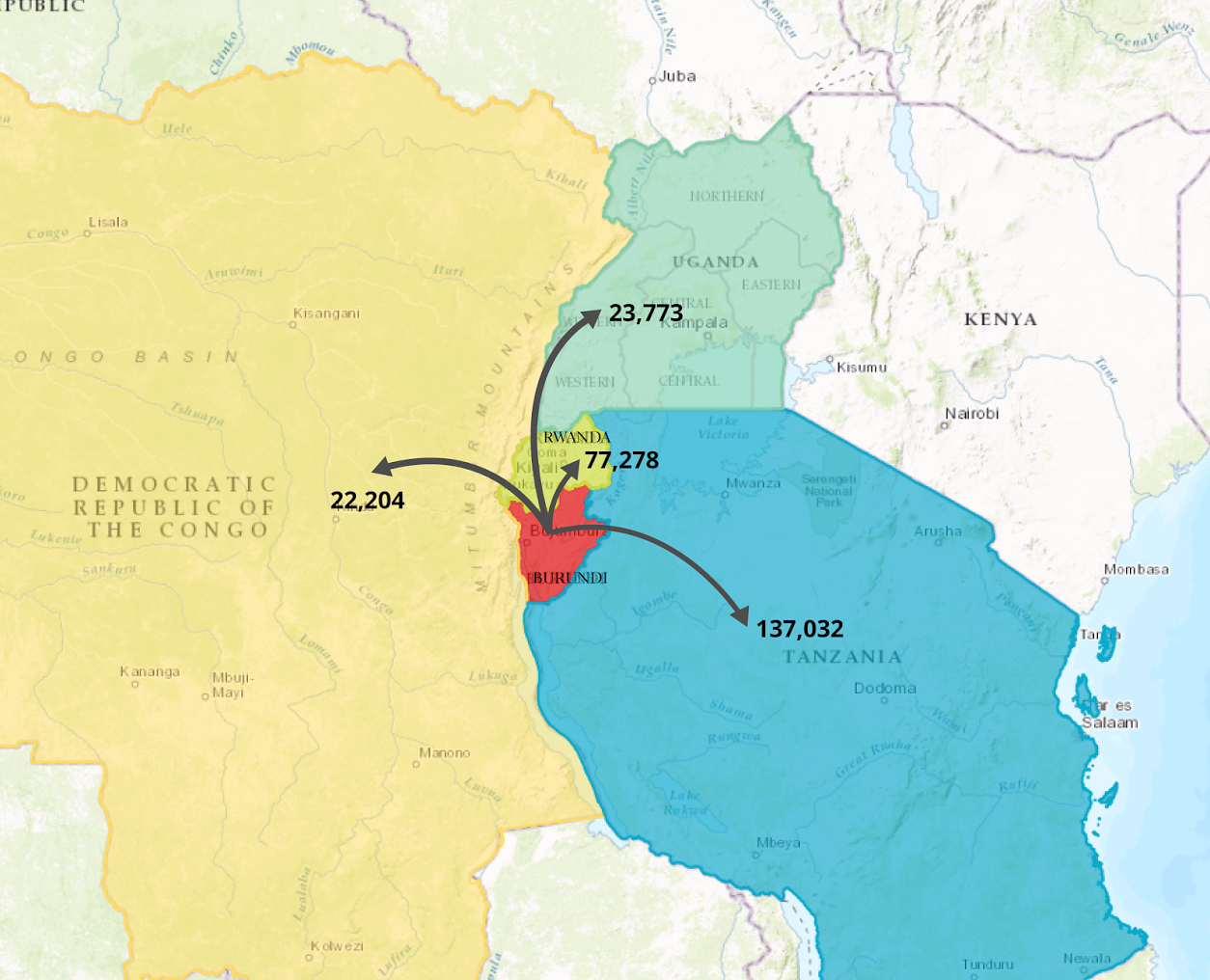

The only alternatives are to become one of the hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing the country or to join the hundreds of Burundians who have already been kidnapped, killed, and dumped in the bush. Opposing President Nkurunziza’s ambitions must seem futile in the face of the very real possibility of detention and abuse by government forces and their allies in the youth militia.

The global community’s efforts to relieve Burundi have been tepid at best. African Union (AU) and United Nations policymakers backed down quickly from pledging peacekeeping troops. Seemingly countless, circular attempts at ‘dialogue,’ were made. Police were dispatched to monitor and advise Burundi’s hilariously corrupt law enforcement apparatus, which isdemonstrably complicit in Nkurunziza’s campaign of violent suppression, to no effect.

Negotiations behind the scenes by a delegation of AU dignitaries have completely failed to secure permission for an African intervention to date. Perhaps the only hint of meaningful action by international actors is the recent opening of a criminal investigation by the International Criminal Court. An investigation might someday result in the prosecution of some of the parties responsible for Burundi’s current climate of insecurity and fear. Perhaps.

Are all of these negotiations a waste of time? President Nkurunziza and his representatives seem happy to blame the conflict on anyone and everyone outside their party. Recent rhetoric seems to assume the existence of ashadowy conspiracy between Rome, Rwanda, NGOs, and every other critic of the Burundian government. Evidence to the contrary is difficult to come by. Broadcast station closures, the arrest of independent journalists, and when all else fails, brazen executions of those journalists and their families keep media under tight control.

The government is covering their tracks and buying time to ensure all other alternatives to a Nkurunziza government have been erased—if foreign parties ever find the backbone to stage an intervention.

For now, there seems to be no reason why this cynical strategy might fail. Unless the international community reverses its course — or ordinary Burundians rise up against the CNDD-FDD en masse and win — Nkurunziza looks very likely to join the ranks of Africa’s presidents for life.

References:

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre and Joakim Karlsen. 2010. Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data. Journal of Peace Research 47(5) 651–660

- Mr. Ndikuriyo delivered his address in the Kirundi language. We derived our quotation from a French transcript of the speech that can be found here.

Curious? Let's set up a free trial.

Try Savanna